Erik Menendez’s Wife Says He’s ‘Deeply Grateful and Profoundly Humble’

After a news conference with nearly two dozen family members and lawyers, Erik Menendez’s wife publicly expressed her husband’s gratitude, speaking out on his behalf on social media.

“Erik feels deeply grateful and profoundly humbled by the overwhelming outpouring of love and support from his family,” Tammi Menendez shared via X. “Their belief in him and encouragement, care, and understanding mean more to him than words can express.”

The family came together from across the country for a historic gathering on Wednesday in the continued fight for the brothers’ freedom outside of the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office.

Lyle (left) and Erik (right) Menendez in the courtroom.

AP Photo

The brothers shot their father, José Menendez, and their mother, Kitty Menendez, a total of 14 times during an attack inside their Beverly Hills home in 1989.

Lyle, who was then 21, and Erik, then 18, admitted they shot their Hollywood executive father and mother because they feared their parents were about to kill them to prevent the disclosure of the father’s alleged long-term sexual molestation of Erik.

In July 1996, both brothers were sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole, a sentence they have been serving ever since. However, new evidence has emerged potentially helping the brothers.

The family members held a press conference in front of the Clara Shortridge Foltz Criminal Justice Center in Downtown Los Angeles. This follows the recent announcement by Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón after his office initiated a review of the Menendez brothers’ case.

Gascón told Newsweek his office is currently reviewing a 1988 letter written by Erik to his cousin Andy Cano about the alleged sexual abuse he endured by his father. The new evidence also includes a statement from a former Menudo member who claims he was also sexually assaulted by José.

Lyle and Erik Menendez admitted they shot-gunned their entertainment executive father Jose Menendez and their mother Kitty Menendez.

IMDb

With a hearing scheduled for November 29, Newsweek contacted the DA’s office to check for any progress on a decision after the family’s press conference. They have not yet responded.

Speakers included Anamaria Baralt, José’s niece; Joan Andersen VanderMolen, Kitty’s sister; Brian Andersen Jr., José’s nephew; and Karen Vandermolen, the brothers’ cousin.

“I struggled to process the events of that fateful August day and the loss I felt,” Anamaria Baralt, José’s niece, said. “Over time, it became clear that there were two other victims that day—my cousins, Lyle and Erik.”

“The truth is, Lyle and Erik were failed by the very people who should have protected them—their parents, the system, and society at large,” Joan Andersen VanderMolen, Kitty’s sister, said.

She continued, “The whole world was not ready to believe boys could be raped or that young men could be victims of sexual violence. Today, we know better. We know that abuse has long-lasting effects, and victims of trauma sometimes act in ways that are very difficult to understand.”

Nearly two dozen family members and the lawyers of Lyle and Erik Menendez held a news conference Wednesday outside the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office as calls for the brothers’ freedom grow.

AP Photos

Brian Andersen Jr., José’s nephew, said, “They are not the same people they were 35 years ago. They’ve shown that they are more than their past. They are survivors; they deserve a chance to rebuild their lives. They are no longer a threat to society.”

“I forgive my cousins,” cousin Karen VanderMolen said. “I have forgiven them forever because I know they were acting out of fear and desperation. These were children—children just six and eight years old—who didn’t understand their own bodies.”

While Tammi did not attend the family conference, she has been actively posting on social media about the brothers’ case, stating, “We continue to pray and ask all of you for your prayers. After 35 years, we just want Erik and Lyle to come home.”

Who is Tammi Menendez?

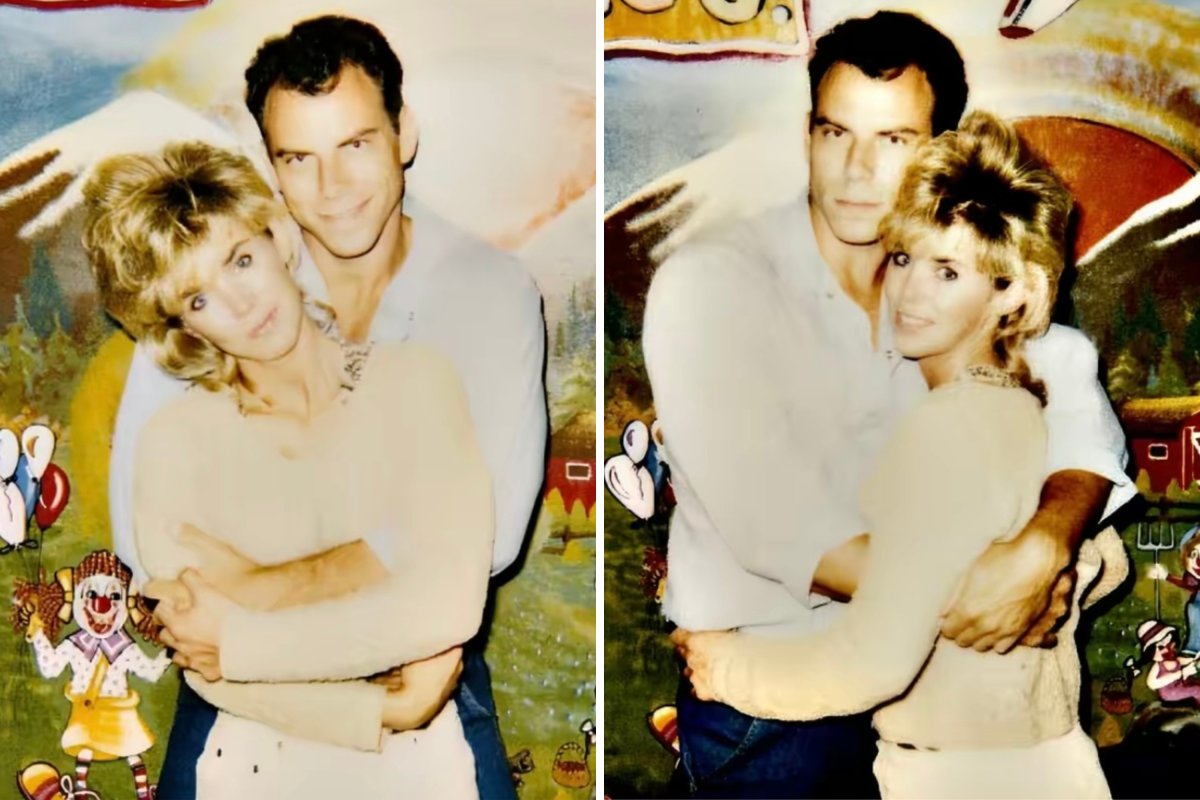

Tammi “Saccoman” Menendez was married to Chuck Saccoman and lived with him when she began following the brothers’ trial on TV in 1993.

Feeling sympathy for Erik Menendez, she wrote him a letter in prison, not expecting a reply. To her surprise, she received one.

Feeling sympathy for Erik, Tammi wrote him a letter in prison, not expecting a reply. To her surprise, she received one.

Tammi Menendez via TikTok

Her then-husband, Chuck, died in June 1996, just a month before Lyle and Erik Menendez were sentenced to life in prison without parole. Following Erik Menendez’s conviction for first-degree murder, he invited Tammi to visit him at Folsom State Prison, where they met in person for the first time in August 1997.

In a 2005 interview with Entertainment Tonight, Tammi admitted she had never visited a maximum-security prison before and felt scared.

“It’s not easy,” she said to the outlet. “You have to go through a lot of checkpoints. And, that’s really, really difficult. Every single day that I drive to the prison, I don’t know for sure if I’m gonna get in.”

Tammi added when she first met Erik, “I could sense that I was attracted to him, but we had been writing for so long that we were like best friends, we talked on the phone a lot and wrote letters for a long time. And so when I first met him, I felt like I knew him. Then it was reality. When he walked in, it was like, there he is. This is real.”

Tammi continued visiting Erik for the next six months, and in 1998, he proposed.

Tammi Menendez via TikTok

Tammi continued visiting Erik for the next six months, and in 1998, he proposed. Although she felt it was a little soon, she was grateful for the proposal, as she couldn’t imagine her life without him.

The two got married on June 12, 1999, in Folsom State Prison. She said in that particular prison, they were strict about visits, stating, “You could only hold hands, and you can kiss when you go in and when you leave. But other than that, that’s it. No conjugal visits, nothing.”

They recently celebrated their 25th wedding anniversary, and Tammi posted on TikTok, “Happy 25th Anniversary on June 12, 2024. Thank you for all your support.”

“I’m glad that I’ve married him and fell in love with him,” Tammi said to Entertainment Tonight. “It has given me a lot of life lessons. And the path that I’m on is a very spiritual, good path. And Erik has really helped me on the path and brought me there. I couldn’t have done it without him. He healed me in so many ways. I don’t think I’d be the person I am today without him in my life.”

Erik Menendez is currently at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility. According to their website, some incarcerated individuals are eligible for “family visits,” which take place in private, apartment-like accommodations on prison grounds and last approximately 30 to 40 hours. However, family visits are not permitted for certain individuals, including those on Death Row, those convicted of sex offenses, individuals in the Reception Centers process or those under disciplinary restrictions.

Lyle Menendez’s Marriage Status

Lyle married twice. His first wife, Anna Eriksson, like Tammi, saw Lyle on TV during his initial trial and decided to write him a letter. Lyle responded to her letter, and their exchange soon developed into a relationship, according to The Sun.

The outlet reported In 1994, Eriksson moved to Los Angeles to be closer to Lyle, taking a job as a contract administrator for a record company.

Anna Eriksson sits in a Los Angeles courtroom Monday, July 1, 1996, as she waits for a judge to make a decision on whether she can marry Lyle Menendez. Superior Court Judge Nancy Brown said she would officiate at the marriage in the county jail. She said she would drive herself to Men’s Central Jail and perform the ceremony.

Ken Lubas/AP Photo

After meeting in person, they fell in love and married in 1996 on July 2, 1996 – the day of Lyle and Erik’s sentencing. Their relationship flourished until 2001, when Eriksson discovered Lyle had been unfaithful with another pen pal. They divorced soon after.

In 2003, two years later, Lyle remarried to Rebecca Sneed. The couple exchanged vows in a ceremony at Mule Creek State Prison near Sacramento, after nearly a decade of knowing each other, a spokesperson told the Associated Press.

In 2003, two years later after he got divorced, Lyle got married to Rebecca Sneed.

Courtesy The Daily Beast

“Our interaction tends to be very free of distractions and we probably have more intimate conversations than most married spouses do, who are distracted by life’s events,” Lyle Menendez told PEOPLE in 2017.

“We try and talk on the phone every day, sometimes several times a day. I have a very steady, involved marriage and that helps sustain me and brings a lot of peace and joy. It’s a counter to the unpredictable, very stressful environment here.”

Getting Married Behind Bars

Terri Hardy, a spokesperson for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, told Newsweek at Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility and Folsom State Prison, all incarcerated individuals are eligible to marry if they meet legal requirements and complete the necessary documents.

Both individuals seeking a marriage license must appear before the county clerk with valid identification and proof of age. The clerk may question them under oath to confirm they meet legal marriage requirements. If one party is incarcerated, the clerk can send a deputy commissioner to the facility or authorize a CDCR employee to gather the necessary information and ensure the inmate is eligible for a marriage license.

Lyle, left, and Erik Menendez leave courtroom in Santa Monica, Calif., Aug. 6, 1990, after a judge ruled that conversations between the two brothers and their psychologist after their parents were slain are not privileged and can be used as evidence in their murder case.

Nick Ut/AP Photo

Hardy said an inmate’s behavior does not play a role in martial eligibility unless the incarcerated person is in restricted housing.

Additionally, no psychological evaluation is conducted and outside input from friends and family members is not considered. However, If the county clerk requests, the staff member handling the marriage process can arrange for a CDCR psychiatrist to assess the inmate’s mental competency.

Marriages at a CDCR facility can be officiated by various individuals, including a priest, minister, rabbi, facility chaplain, or a chosen religious figure with gate clearance. Other authorized officiants include current or former judges, magistrates, commissioners of civil marriages, or county clerks.

Nonprofit religious officials may also perform ceremonies if licensed. Members of religious groups without clergy can conduct marriages by attaching a statement to the marriage license, detailing the religious society, ceremony details, and witness signatures.

Hardy said the ceremony must be held in the institution’s visiting area.

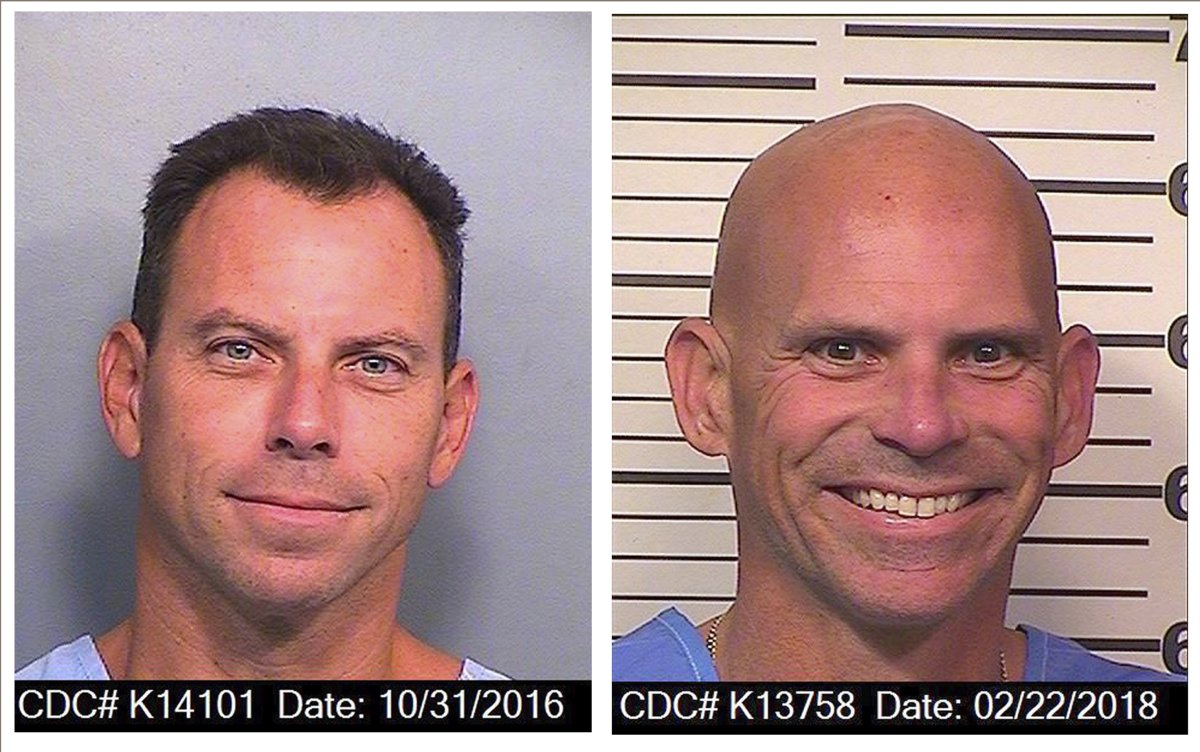

An Oct. 31, 2016 photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Erik Menendez, left, and a Feb. 22, 2018 photo provided by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation shows Lyle Menendez.

California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation/AP Photo

Newsweek spoke with Ashley Nellis, a scholar on life imprisonment, who highlighted the challenges faced by both those serving life sentences and their family members. She emphasized if an inmate chooses to marry in prison, the person on the outside must understand the situation is “unlikely to change.”

“They [the family] certainly face the loss of that person,” Nellis said. “If it’s their parents, spouse, or sibling, they will never again see them except in the visiting room, which has restrictions.”

She also said, in some cases, it’s not uncommon for inmates serving life sentences or their loved ones to choose to cut off contact.

“It’s so difficult keeping up with that relationship for the rest of someone’s life,” Nellis said. “For lifers they will often say that they want to relieve their family member of that burden of coming to visit them.”

Nellis continued, “For family members, it’s a lot to manage. It’s very difficult to communicate with people in prison and it’s very expensive. There’s a real racket in the phone companies that have contracts with prisons where they can charge enormous amounts of money to get a phone call or an email sent through.”

Do you have a story Newsweek should be covering? Do you have any questions about this story or the Menendez Brothers? Contact LiveNews@newsweek.com